Источник данных – БВО «Амударья», аналитическая обработка — НИЦ МКВК. Как сообщается в бюллетене МКВК, данные представлены с целью оперативного оповещения и могут быть впоследствии уточнены.

DROP BY DROP

Мы продолжаем эксперимент с английским на sreda.uz. Русская версия была опубликована и называлась \»Пионеры капельного орошения\» water

Мы продолжаем эксперимент с английским на sreda.uz. Русская версия была опубликована и называлась \»Пионеры капельного орошения\» water

Uzbek farmers have traditionally relied on a system of canals and irrigation ditches to bring water to their crops; but with water increasingly scarce, many are turning to new drip-technology. Water-saving new technology in Central Asia

Water-saving new technology in Central Asia

Uzbek farmers have traditionally relied on a system of canals and irrigation ditches to bring water to their crops; but with water increasingly scarce, many are turning to new drip-technology.

First Time in the Fergana Valley

To get to the Fergana Valley you have to cross the Kamchik pass. The air is thin up here, and close to the snowfields are bright green slopes. The Fergana valley looks like a pear, cut in two by the Syrdarya river and its tributaries, and criss-crossed by the irrigation canals branching off them. Descending from the pass into the valley, the first thing you notice is the edge of the pear – empty steppe where no water reaches. The scarcity of water in the summer heat is palpable, even this close to region’s main water artery.

When Abdulvokhid Boltaboyev decided to set up a drip irrigation system on his farm, his neighbours were sceptical. Most people here are accustomed to using water carried by a system of irrigation ditches and channels from a nearby canal. But tradition has its drawbacks: when the ground is waterlogged, ground water rises carrying salt. At the height of summer the supply of water is greatly reduced, and the fields at the further end of the irrigation systems go unwatered. The deficit has started to cause tensions, with neighbours surreptitiously siphoning off one another’s supplies. As a result, the “battle for the harvest” ends with modest results.

When Abdulvokhid Boltaboyev decided to set up a drip irrigation system on his farm, his neighbours were sceptical. Most people here are accustomed to using water carried by a system of irrigation ditches and channels from a nearby canal. But tradition has its drawbacks: when the ground is waterlogged, ground water rises carrying salt. At the height of summer the supply of water is greatly reduced, and the fields at the further end of the irrigation systems go unwatered. The deficit has started to cause tensions, with neighbours surreptitiously siphoning off one another’s supplies. As a result, the “battle for the harvest” ends with modest results.

The yields from the land plots on the old river bed in the Uichinsky district of the Namangan region are not great. The river changed course long ago. But although the local farmers who divided up the former floodplain gathered and removed the stones from the dry river bed, the quality of the land remains poor.

The yields from the land plots on the old river bed in the Uichinsky district of the Namangan region are not great. The river changed course long ago. But although the local farmers who divided up the former floodplain gathered and removed the stones from the dry river bed, the quality of the land remains poor.

“It is not a place worth experimenting with,” the neighbours said. But Abdulvokhid thought differently. In 2009 he began to experiment with two different systems of drip irrigation on five hectares of cotton fields, and that Autumn he gathered 38 quintals of cotton per hectare. His neighbours brought in a maximum of 20.

After gathering the harvest, Abdulvokhid went to China study that country’s experience with drip irrigation. In the end, he decided not only to use the system on his own land, but decided to set up his own business producing the systems in Uzbekistan.

After gathering the harvest, Abdulvokhid went to China study that country’s experience with drip irrigation. In the end, he decided not only to use the system on his own land, but decided to set up his own business producing the systems in Uzbekistan.

He took out a $92,000 bank loan to buy the equipment from China he needed to start production, and sought further support from the Global Environment Facility’s local branch in Tashkent.

The GEF launched small grants program in Uzbekistan in 2008, and it already supports more than 50 projects dealing with biodiversity, climate change adaptation, and land degradation. Like all applicants, Abdulvokhid was expected to put own finances into the project too: the fund will only provide co-financing, covering no more than 50-percent of the costs of a project.

When Abdulvokhid invited experts from the GEF grants program to see how drip irrigation working on his fields, they came away impressed. They found that he’d achieved significant savings in water and fertiliser and halved his average electricity consumption.

When Abdulvokhid invited experts from the GEF grants program to see how drip irrigation working on his fields, they came away impressed. They found that he’d achieved significant savings in water and fertiliser and halved his average electricity consumption.

Thus the GEF launched a three year project called “Drip Irrigation in the Fergana Valley.” Abdulvokhid got a $50,000 grant to start production and buy raw materials. His contribution was equipment and a commitment to provide one hectare’s worth of drip irrigation free of charge to 20 farmers across the republic. In 2012, he started production.

Greenhouses on the Hills

Along the northern channel of the Namangan canal, pumps steadily push water up to the hilly Adyrs. The Adyrs are the foothills of the Fergana valley, made up of the degraded material of the mountains. Although watering land on the Adyrs via irrigation ditches takes a great deal of water, the fields are still for the most part irrigated in the traditional way. The landscape is a patchwork of verdant hillsides painted with green wheat fields and brown arable land, a vineyard here, an orchard there.

Along the northern channel of the Namangan canal, pumps steadily push water up to the hilly Adyrs. The Adyrs are the foothills of the Fergana valley, made up of the degraded material of the mountains. Although watering land on the Adyrs via irrigation ditches takes a great deal of water, the fields are still for the most part irrigated in the traditional way. The landscape is a patchwork of verdant hillsides painted with green wheat fields and brown arable land, a vineyard here, an orchard there.

In one of these orchards, says Abdulvokhid, his father introduced drip irrigation to Uzbekistan for the first time when he used nails to drive holes into a hose in 1968. By attaching buttons in a cunning arrangement, the story goes, he was able to let water drip under the trees.

But there was little demand for drip irrigation in Soviet times. Water was plentiful, and the Toktogul reservoir upstream in Kyrgyzstan provided all the irrigation anyone needed. All the water accumulated over the winter flowed to the fields in summer. “When the Soviet Union collapsed, much changed. I got myself 70 hectares, became a farmer, But I found that when the crops needed water, there simply wasn’t enough. That’s when I remembered what my father had told me about drip irrigation,” recalls Abdulvokhid.

But there was little demand for drip irrigation in Soviet times. Water was plentiful, and the Toktogul reservoir upstream in Kyrgyzstan provided all the irrigation anyone needed. All the water accumulated over the winter flowed to the fields in summer. “When the Soviet Union collapsed, much changed. I got myself 70 hectares, became a farmer, But I found that when the crops needed water, there simply wasn’t enough. That’s when I remembered what my father had told me about drip irrigation,” recalls Abdulvokhid.

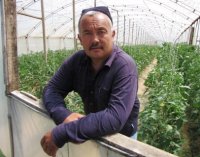

Amongst the first to decide to try out drip irrigation on the Adyrs and turn to Abdulvokhid for advice was Nosirzhon Saifullayev, who farms two hectares with onions, an orchard and a melon field. His hillside smallholding can now be easily identified by the two white plastic polytunnels, each at least 50 metres long.

Nosirzhon started putting up the first of these green houses for vegetables last year. For the first three days he watered them through holes in the roofing material, but the water did not reach the back rows. It was at this point Abdulvokhid suggested he join the drip-irrigation project. Together they calculated the cost of installation, and put in the system in spring. The system is pretty simple: water is pumped from an irrigation ditch into a barrel at the top of the property, and gravity does the rest, guiding the water down tubes to the crops.

Nosirzhon started putting up the first of these green houses for vegetables last year. For the first three days he watered them through holes in the roofing material, but the water did not reach the back rows. It was at this point Abdulvokhid suggested he join the drip-irrigation project. Together they calculated the cost of installation, and put in the system in spring. The system is pretty simple: water is pumped from an irrigation ditch into a barrel at the top of the property, and gravity does the rest, guiding the water down tubes to the crops.

Nosirzhon wants to add another greenhouse, and he will plant his next crop in September, so he will be able to harvest tomatoes and cucumbers by New Year. “I’ve filled the barrel with five tons of water for insurance. My water consumption is lower now – it would be difficult to use any less. I dream of using drip irrigation on the whole farm,” he says.

The GEF’s experts have confirmed the impressive water savings that can be made when irrigation is delivered drop-by-drop. According to Alexei Blokov, the head of the grants program in Uzbekistan, almost all the water reaches seedlings’ roots. “It is nearly 90 percent efficient. You can supply it from any local water source – springs, rivers, lakes. It cuts losses to evaporation during transportation from the source to crops. The system is very simple to use and cheap to install and service,” he says.

The GEF’s experts have confirmed the impressive water savings that can be made when irrigation is delivered drop-by-drop. According to Alexei Blokov, the head of the grants program in Uzbekistan, almost all the water reaches seedlings’ roots. “It is nearly 90 percent efficient. You can supply it from any local water source – springs, rivers, lakes. It cuts losses to evaporation during transportation from the source to crops. The system is very simple to use and cheap to install and service,” he says.

State support

Abdulvokhid, Nosirzhon, and many other farmers have already proved the potential of micro-irrigation, and the Uzbek government has taken notice. In the summer of 2013 the government passed a resolution to support adoption of the  technology, including financing installation of drip-irrigation systems and other water saving technology. The plan is for drip irrigation to be introduced to all areas suffering from chronic water shortages, as well as land where the topography makes delivering water expensive. Priority will be given to orchards, vineyards, melon fields, and other high-profit crops.

technology, including financing installation of drip-irrigation systems and other water saving technology. The plan is for drip irrigation to be introduced to all areas suffering from chronic water shortages, as well as land where the topography makes delivering water expensive. Priority will be given to orchards, vineyards, melon fields, and other high-profit crops.

Some calculations suggest the new technology could save an average of 65 percent of the water currently used on cotton production and 54 percent of that used on fruit and vegetable cultivation, while at the same time increasing yields. Incentives already on the table include a special credit line by the Ministry of Finance’s land reclamation fund offering famers preferential-rate three year loans of up to $28,000, and the opportunity for farmers to use the volume of water they save on other fields. Other measures in the pipeline include exemptions from land tax and support for buying polytunnels.

Drip irrigation supplied water to just 1,400 hectares of agricultural land in Uzbekistan in 2013, and is set to grow to 25,000 hectares by 2018. That is still only a fraction of the more than 3.5 million hectares of farmland in the country. But with water shortages and the pressures of climate change getting worse with each year, drip irrigation in Uzbekistan is promising, economically attractive, and environmentally friendly.

Drip irrigation supplied water to just 1,400 hectares of agricultural land in Uzbekistan in 2013, and is set to grow to 25,000 hectares by 2018. That is still only a fraction of the more than 3.5 million hectares of farmland in the country. But with water shortages and the pressures of climate change getting worse with each year, drip irrigation in Uzbekistan is promising, economically attractive, and environmentally friendly.

Nataliya Shulepina,

Photo by the author

sreda.uz

Russian version water

|

Добро пожаловать на канал SREDA.UZ в Telegram |

Еще статьи из Вода

Столетию САНИИРИ — сейчас это Научно-исследовательский институт ирригации и водных проблем — была посвящена состоявшаяся Ташкенте международная научно-практическая конференция.

Как чувствуют себя памирские ледники и амударьинские тугаи в эпоху активного вмешательства человека в природу? На эти вопросы предстоит ответить исследователям из стран, откуда сток, и стран, где он «рассеивается». Здесь: про Памир и «Тигровую балку».

Сборник научных статей будет сформирован по итогам конкурса статей. Конкурс объявлен Научно-информационным центром Межгосударственной координационной водохозяйственной комиссией (НИЦ МКВК).

Всемирный день борьбы с опустыниванием и засухой отметили 17 июня. ООН провела его под девизом «Восстановление земель. Новые перспективы». Прилагаем к тексту фото Наталии Шулепиной из Байсунского района Сурхандарьинской области Узбекистана.

Исследование предлагает универсальную методику, позволяющую объективно измерить деградацию рек и ставит под сомнение устоявшееся представление о малой гидроэнергетике как о безоговорочно «зеленом» источнике энергии.

На 69-м заседании Совета Глобального экологического фонда (ГЭФ), прошедшем в Вашингтоне, принято решение провести 8-ю Ассамблею ГЭФ и 71-е заседание Совета ГЭФ в 2026 году в Самарканде.

Водный форум состоялся накануне Международной встречи в Душанбе по ледникам. Тема форума: «Усиление трансграничного сотрудничества во имя водной и климатической устойчивости в бассейнах Центральной Азии, зависящих от ледников». Итак, май 2025-го.

Офис Международного союза охраны природы (МСОП), открывшийся в Ташкенте, будет работать в странах Центральной Азии. Церемония открытия состоялась в Центрально-Азиатском университете по вопросам экологии и климата (Green University). Здесь и будет базироваться региональный офис.

Цель — поучаствовать в Водном форуме и посетить заповедник «Тигровая балка». Здесь — фоторепортаж о городе.

Что может гореть в пустыне?

Комментарии из Телеграмм-канала sreda.uz:

- Z A: Это газовое месторождение по среди пустыни. Я почти рядом проезжал от этого факела. - Anna Тен: Мы такое видели около Талимаржана лет шесть назад. Нам сказали, что в газовых трубах, которые идут с места добычи, оседает мазут и что так очищают трубы газовые от него. Не знаю, это правда или нет. - Наталия Шулепина: Спасибо, теперь понятнее. Факел не виден. Вот около экоцентра Джейран, там факелы видно. Здесь просто дым. - Хасанов: Газовые трубы очищают, а мазут - в окружающую среду?! Дешево и сердито?!

Рассеивание водного стока от памирских высот до амударьинских тугаев

Спасибо, Наташа! Как всегда, отличный познавательный репортаж с фотографиями. с уважением, Муазама Бурханова

Туркменский опыт: сады и теплицы на неудобьях. Фисташка

Евгений

Хотелось бы увидеть обзорный репортаж о берегах Аму-Дарьи , фото , рассказ о поселения людей, их хоз.деятельности

Как приумножить леса в Узбекистане?

Матильда

Возле ЦУМа в парке растут колонновидные дубы и конские каштаны. Насколько они могут прижиться на склонах холмов и адыров?

Туркменский опыт: томаты и сертификаты

Ангелина

Очень познавательно! Как бы сделать такой же репортаж с такими же подробностями про теплицы в Узбекистане.

На улице Ульяновской в Ташкенте

Очень тёплые фотографии.

Законодатели рассмотрели включение в законодательство Узбекистана нормы об отмене права на землю

Ангелина Борисовна Однолько

То есть земля станет настолько дорогой и невыгодной; что люди перестанут заниматься с/х? Или в итоге это приведет к росту цен на с/х продукты?

Вызовите свидетелей, проверьте доказательства и судите

admin

Как журналисту, мне много раз приходилось бывать на судебных процессах. Разных. Был даже процесс, когда судили инженера и дали срок за то, что компания, в которой он работал, предложила своим клиентам Скайп. Тогда это было внове. Насчитали в суде огромный ущерб государству, ведь благодаря интернету люди стали меньше пользоваться междугородней телефонной связью. Руководитель компании успел выехать из Узбекистана, а на инженера, как только он по повестке пришел в прокуратуру, надели наручники. Суд его приговорил к тюремному заключению. Поэтому возникает вопрос об ответственности следствия и судей. Как известно, Скайп и Вотсап очень быстро вытеснили междугородную телефонию. Мне этот случай запомнился. Обвинения сотрудникам Госбиоконтроля в нанесенном ущерба государству из того же ряда. Четырех с половиной миллиардов сумов ущерба, оказывается, не было. Восемь лет понадобилась, чтобы суд сделал такое заключение. Еще ряд обвинений не снят. Подождем. А вот с этой колоссальной сумой как быть? Кто-то же ее насчитал!

Вызовите свидетелей, проверьте доказательства и судите

Алия

100 % заказная проверка, организованная бывшим председателем Госкомприроды Абдусаматовым, падким до огромных барышей. И к слову сказать, впоследствии снятым с должности председателя и севшим за решетку за взятку. Я работала в комитете в пору его "правления". Наше управление тоже прошло через жернова этой заказухи. И тоже было шито все белыми нитками и высосано из пальца. Лично знаю и Григорьянца, и его бухгалтера Татьяну, в курсе всего того безобразия, что творили с Госбиоконтролем. А вся беда Госбиоконтроля лишь в том, что через его счета проходили большие деньги. Конечно же, целью проверки и ее неоправданно раздутой масштабностью было очернить и убрать с должности Григорьянца, а на его место посадить "своего" и грести лопатой себе в карман бюджетные средства. Очень хочется надеяться, что в конце концов в этом деле будет поставлена точка с благополучным концом - снятием всех выдуманных обвинений. К слову сказать, со всех других сотрудников различных управлений Госкомитета все обвинения сняты в результате их многолетних хождений по судам. Отдельное спасибо автору публикации за проделанную титаническую работу. Будем надеяться, что правосудие наконец-то свершится.

НА ТЕКТОНИЧЕСКИХ ПЛИТАХ

Лия

Здравствуйте. Очень познавательная и интересная статья. Большое спасибо Г. ПЕРЕВОЗЧИКОВУ и АТОСУ за прекрасные комментарии. Такие статьи с примерами необходимо преподавать в школах в современном Узбекистане. Хотела почитать, на какой плите находится Узбекистан, и через сколько лет будет очередной сдвиг с соседней плитой, а столько интересного узнала. СПАСИБО!!!